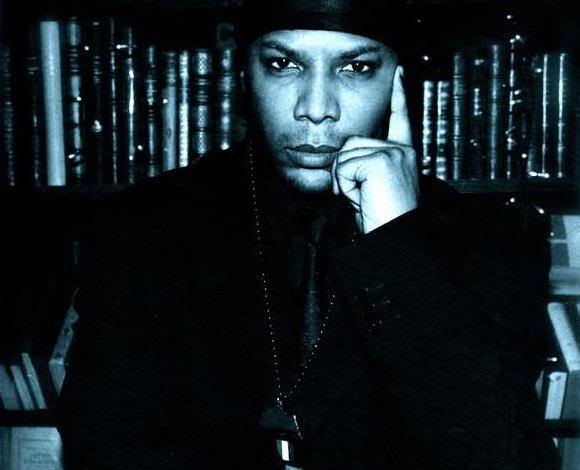

Originally from the South Bronx, globe-trotting hip hop activist Dynamax has toured all over the world and currently represents the US Embassy as their Hip-Hop Ambassador and Cultural Specialist.

Originally from the South Bronx, globe-trotting hip hop activist Dynamax has toured all over the world and currently represents the US Embassy as their Hip-Hop Ambassador and Cultural Specialist.

Representing old school hip hop, Dynamax has worked with some of the greats, including DJ Kool Herc, Afrika Bambaataa, Chuck D (Public Enemy), Lord Jazz and DoItAll Dupré (Lords of the Underground), and countless others.

As an ambassador, Dynamax has also spent a lot of time teaching hip hop culture and business techniques in schools, outreach programs, and colleges in a dozen African nations.

More recently, Dynamax has wrapped up Under Dog Nation Volume 1 with his Years of the Canine group, a fusion of punk and hip hop rich with features, production, collaboration and composition from the likes of legendary rock writer, critic and producer Kris Needs, Dom Beken, Guy Pratt (Pink Floyd), and Headcount. The album will drop sometime in January 2016.

Say Hey There sat down with Dynamax to reminisce about old school hip hop and listen to his passionate belief that teaching others about the culture’s roots and keeping the true meaning behind the elements of hip hop alive is vital to community relations.

Say Hey There: Let’s start by talking about your childhood. How did you become involved in hip hop?

Dynamax: I was born and raised in the Bronx. The music in my DNA comes from my father from Tennessee, a guitarist, and his whole family was very musical. I met my dad when I was 9 years old, which is a weird story but true. The first gift I got from my dad was a pair of bongos, then I got a bass guitar. And growing up in NYC, my older brother was always DJing. He had the turntables on my grandmother’s ironing board. He looked like a scientist to a six-year-old kid. The music they was playing was hip hop anthem kind of tracks. My childhood was a mix of things. It’s a rich background of different styles.

Before the word hip hop could even come into play, trains were covered in graffiti. It was amazing to see growing up. My sister would sneak out of the house and take me to the parks where Grandmaster Flash or Afrika Bambaataa was playing. That’s how I got exposed to hip hop. We’d see b-boying. The commercial title was breakdancing, but it was called b-boying. You would see that in New York on the streets and the big boomboxes and cats dancing. Hip hop was completely illegal. They got arrested for doing graffiti. Sometimes kids got arrested for soliciting money for dancing on the street. If you DJd in the parks, you basically stole electricity from the lamp posts to DJ. So all 4 elements were completely illegal.

We weren’t allowed to play hip hop music in the clubs. We were a grassroots, street culture because we were in the streets or we were in the parks. Afrika Bambaataa had the connection with the community centers and Kool Herc had the connection to use the recreation room to throw the first hip hop parties. The magic started in the recreation room and the parks. This is how I saw hip hop growing up. Fast forward to the future for myself, I couldn’t help but to be an MC or a DJ. It was something that was always on the radio, always part of the culture. At 11 and 12 I started teaching myself how to freestyle and DJ. I begged my father to get me turntables but he always thought it was too expensive or just a fad.

Hip hop was completely illegal. They got arrested for doing graffiti. Sometimes kids got arrested for soliciting money for dancing on the street.

Say Hey There: How did it evolve into a career?

Dynamax: After doing talent shows and making demos between 16 and 19, I got contacts in New York through a friend of mine, a very famous graffiti artist named Zimad. He connected me with a woman named Barrie Cline dealing with art galleries in Manhattan. I became friends with her and talked to her about what I wanted to do with my music and my message. I was always about the 4 elements of hip hop. She had one musical contact with a guy named Montecristo, who was the road manager for George Clinton. She connected me with Monte and I hung out with him for about a year. One night he called me and said “Do you want to make a record?” I said of course. The next day my group and I went to the studio and made two tracks.

Say Hey There: How did you hook up with Afrika Bambaataa?

Dynamax: I toured Europe 6 months after making that first record. We came back to America, and I kept involved with the culture, going to events that Kool Herc or Afrika Bambaataa were doing. I had an affiliation with the Herculoid family and became almost like a musical son to Herc in a business sense as a liaison for the Herculoid family in Europe. Then I connected with Kay Dee, and he was the one telling Africa about me and what I was doing in Europe, and Afrika said, “You should ask him if he wants to get down with Zulu Nation.” Even if I was already rolling with Kool Herc.

Say Hey There: Did Bambaataa create Zulu Nation?

Dynamax: He was one of the founding fathers. He didn’t by himself create it. Big shoutout to Ahmed, he’s the other half of that coin.

Say Hey There: So Bambaataa asked you to join Zulu Nation, and you of course said “Yes”?

I was going to go live in Europe in 1998. The zulu nation chapter had died out in France, and they asked me to help bring it back. For me it was an honor.

It took me about four years to do it. I was on the radio out there. I was signed to Universal on a special projects and publishing deal. I was already collaborating with a lot of artists with Universal anyway so they were like we might as well sign you.

Say Hey There: What does resurrecting Zulu Nation in France involve?

I had a radio show called “Live from New York.” I was DJing, MCing, hosting my show, playing the break beats for bboys and bgirls, and did a lot of hip hop and R&B. Before the internet blew up, they couldn’t get all the music that we had, so I was going to NY and coming back with all the latest records that they didn’t have. They don’t need us anymore, but I’m happy they still page homage to hip hop and the Bronx.

France is only ten years behind America. Hip hop started there in ’81 or ’82. Hip hop is 41 years old. It became a genre in 1986 because of Run DMC and Beastie Boys crossing over and they could no longer see us as a pop record; we had to have our own category.

Hip hop is 41 years old. It became a genre in 1986 because of Run DMC and Beastie Boys crossing over and they could no longer see us as a pop record; we had to have our own category.

Say Hey There: At what point did you get involved with Ice T’s Rhyme Syndicate family and the Bronx Syndicate with Donald D?

In 2000 I had the chance to connect with Donald D, who was the first Rhyme Syndicate artist that Ice T signed. Donald D introduced me to Afrika Islam, and they inducted me into the Rhyme Syndicate in 2008. The Bronx Syndicate is a spin-off with me and Donald D within the Rhyme Syndicate. It’s not really fully operating right now, I’m trying to get it back on track and breathe new life into it.

I’m really proud to be a part of that team, that family. It’s a page in the culture of hip hop. Ice T was the first rapper from the West Coast to come out, one year before NWA. And being that Afrika Islam, the son of Bambaataa produced Ice T, says a lot about the West Coast and East Coast in hip hop; hat we gave birth to the West Coast, of course we did, but we like to stay humble and quiet about it so the West Coast can have their Shine. Ice T was born in New Jersey and Tupac was born in Harlem.

Editor’s Note: Watch Dynamax and Donald D in this video for “The Funhouse Adventure.”

Say Hey There: Let’s talk about becoming an ambassador for the US Embassy. Is that related to Afrika Bambaataa’s Zulu Nation? How did that happen?

Dynamax in the United Kingdom for the 42nd Anniversary of Zulu Nation, accepting the lifetime achievement award from Donald D.

Dynamax: I am an ambassador for Zulu Nation, that’s one side of the coin, and I’m also an ambassador for the government representing the social movement, and that’s different.

I got involved because a young sister named Tracy – who goes by her artist name L.S. – told me that the US Embassy was looking for hip hop artists.

I went in and had a meeting with Marion Salvanet, the French representative of the US Embassy, and gave them a press kit. They were impressed and asked “What do you do when you’re not doing this?” I said I’m teaching hip hop in a couple elementary schools maybe four times a week. They said this is really interesting, we need you to write up your programs and what you can bring to the table. I came up with the upliftment of women in hip hop, how African American culture relates to Africa, teaching about the elements of hip hop, and a crash course of the music industry.

They proposed my workshops to different folks in Africa and six months later I got nominated to go to Luanda, Angola and Nigeria. I got lucky to go once, but I kept asking to go back and go back. I ended up going to 12 countries and started to become official. They gave me the title of Cultural Specialist Hip Hop Ambassador.

They didn’t know they were getting Dynamax. They thought they were just getting a regular rapper who would go out there and perform or DJ for the kids, but I went in with a message and a certain way I carried myself, spoke, and dressed. I can speak slang like I do when I’m in the Bronx with my peers, but when I’m on the radio and representing our country internationally, I’m not putting on an act. This is how I speak professionally. That’s how I kept the job.

Say Hey There: Paint me a picture of what it’s like to go to one of these African countries and lead a workshop.

Dynamax: We do everything. Sometimes I go into a workshop with a bunch of DJs and will speak to them about the knowledge of being a DJ, from being a radio DJ to a club DJ to a DJ for a group or band. In some parts of Africa I would do a workshop outside. Sometimes they couldn’t find a community center and put me in a church with 950 kids. The US government would organize them.

Say Hey There: Why does the embassy care?

Dynamax: That was the first question I asked when I met with them. The kids are fascinated by it because it’s popular in American culture, and they felt that music could be a great vehicle to reach the youth. It’s all about relations. At the time that I went, they said okay, we’re going to send in the military to help build schools, find clean water, and share resources and at the same time send in a music program for the kids to try to inspire them and do something to help their self-esteem.

Say Hey There: What was the underlying message that you were supposed to bring to these other countries?

The message that I brought Africa was about working together, about community.

The message that I brought Africa was about working together, about community.

I gave them the knowledge of the hip hop story: about how it was created with no money, we didn’t have the industry behind us, and people said it wasn’t art, that it was a bunch of noise. It was misunderstood from the front gate. When the media image came out and people started stealing from hip hop, corporate America started taking what they wanted from it. They took a breakdancer and made a corny cereal commercial. That’s how hip hop started getting watered down, polluted, and distorted. We came out with MC Hammer, now we got Vanilla Ice. We came out with New Edition, now we got New Kids on the Block. It was like for every hardcore hip hop element that came out, we got a watered down, commercialized version of it. Public Enemy came out and smashed the whole game with a real positive, uplifting message about coming together, black pride, and stopping self-destruction.

They wanted to hear the message that hip hop truly represents, and the message is peace, love, unity, work together as a community.

I gave them the knowledge of the hip hop story: about how it was created with no money, we didn’t have the industry behind us, and people said it wasn’t art, that it was a bunch of noise.

Say Hey There: As someone who has essentially been around since the beginning, do you feel like some artists today aren’t doing the hip hop culture justice?

Dynamax: Either you’re hip hop or you’re not. Lil Wayne was just inducted into Zulu Nation. For me there’s nothing to talk about there because we open our door to everybody who wants to be more positive and take their hip hop knowledge to the next level. Nicki Minaj, everybody. I do say to the people doing negative messages that you need to tighten it up and give us something a little more positive. I say to the people that are doing something more positive, you need to speak out more and continue what you’re doing. Big shoutout to KRS-One, Common Sense, Immortal Technique, and artists like Talib Kweli and Mos Def.

Say Hey There: But in another sense, part of your message is the “return” of the hip hop culture.

Because the culture and image of hip hop itself got distorted by being kidnapped by the corporate world, so therefore people have a misconception that hip hop is only rap music. The corporate world took that word and said we’re going to sell this as if it’s only the music side and say that’s hip hop period. No, hip hop has elements and it’s the baby of the Zulu nation. It’s only one of our creations.

Say Hey There: What are you promoting right now?

Dynamax: I’m promoting a punk rock, alternative band called Years of the Canine. It’s a supergroup with Afrika featured, Guy Pratt of Pink Floyd, a group called Headcount, and Donald D. The producer and mastermind behind the sound is Dom Beken. I’m the lead vocalist of the project.

There you have it, kids. Make sure to check out the video for “Resurrected Angel,” filmed by Nebraska music video director Aaron Gum.

Follow

Recent Comments